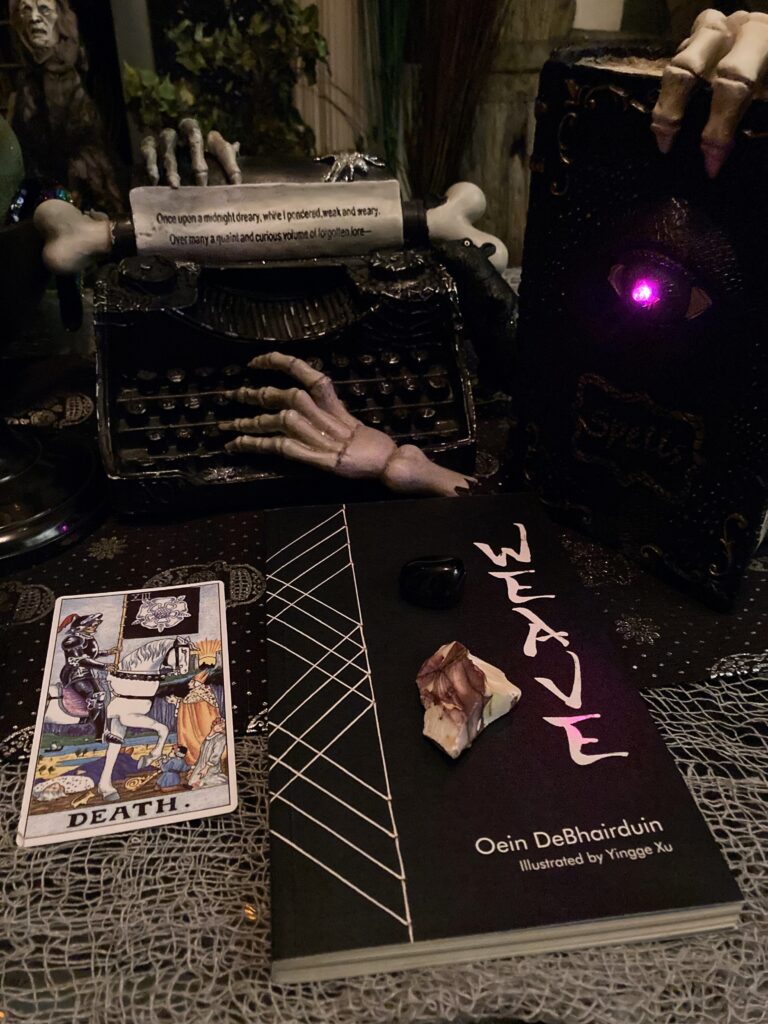

Part of the Wheel of the Year Series inspired by Weave by Deirdre Sullivan and Oein de Bhairduin. This story was written for Samhain.

A Penanggalan in Transylvania

29th October. Brasov, Transylvania. Left London at 10.30am, on 27th October, arriving at Bucharest late that evening; should have arrived at 5.30pm but the flight was an hour late…

I disproportionately enjoy starting my journal entry for my 35th birthday trip to Transylvania in the same format as Jonathan’s Harker’s in Dracula. I have brought it along with me on the train from Bucharest through the Carpathian mountains, now gloriously dressed in its autumnal gowns. I have never seen such colours on the trees- the gold and ochre of beech and deep carmine-red pine against forest green spruce, and every so often, the rising spire of a diaphanous silver fir. They are plucked from the shadows and glow in spotlit golden swathes like little forest fires. Deep within, bears lumber and wolves prowl, and the Carpathians, like a great, curled, sprawling beast, threaten at any moment to swallow the pretty villages like Brasov which nestle at its feet.

I am struck by a paragraph on the first page which had never before captured my attention:

“I read that every known superstition in the world is gathered into the horseshoe of the Carpathians, as if it were the centre of some sort of imaginative whirlpool; if so my stay may be very interesting.” I wonder if such superstitions could extend as far as my own lineage, to my mother’s side in Malaysia or my father’s in India.

I am bound for Brasov to present at a Dracula Conference coinciding with my 35th birthday.

Before leaving, I visited my parents in our family home in Dublin. My mother had been more solemn and emotional than usual.

“In our family, Chinta, a woman’s 35th birthday is very important,” she said. “Still no man, Isha? No children on the way? What about that nice doctor you were dating?”

My last boyfriend had only a PhD in English Literature but my parents liked to fixate on the technicality of his being a doctor.

“No Ibu, we’re not seeing each other anymore, remember? We wanted different things.”

“And what is it that you want, eh, Chinta? You don’t want a family?” Every year she had grown more distressed as the prospect of my having children grew ever more distant. This year I sensed a change in her- something closer to resignation.

“I do want a family Ibu, but it’s not my fault if it doesn’t happen for me. Is it so bad if I don’t end up having children? What about Siti Auntie? She’s happy, isn’t she?” Siti Auntie, always glamorous and windswept, would bring us trinkets from her travels around the world and enchant me with bedtime stories of fairy tales and myths she picked up on her adventures. As a teenager she showed me how to wear her signature red lip, and although I shared her silky black hair, my mother would not let me wear it as long as hers, which tumbled all the way down to her hips.

“Hayo, always you want to be like Siti Auntie. No matter what I tell you.” We were standing alone in the kitchen after dinner, putting away the dishes. “I have something to give you, Chinta. Stay there.” She went upstairs while I stared at my reflection in the window over the kitchen sink. No crow’s feet yet. The marionette lines at the corners of my mouth were deepening. I felt a sense of finality as the axe came down on the first half of my life, and realised that I was really and truly no longer young.

My mother returned and in her hand was an old, faded green, leather-bound journal. She handed it to me. Its thin tawny leaves were falling out and barely held together, the binding worn, the ink I glimpsed was almost translucent.

“For over a century, this book has been handed down to the women in our family Chinta, always when they turn 35.”

“Why wait so long?” I asked. “Isn’t 16 to 21 the usual age for passing on heirlooms and that sort of thing?”

“At 16 or 21 you are still girlish, you think you have the rest of life ahead of you. You are full of youth and beauty. At 35, all that is gone-”

“Hey!”

“But this is when you really have become a woman. Just take it with you on your birthday trip.”

It sits in front of me now, this withered ancestral relic. My mother gave no hints of what it contains, which feels very strange for what I have grown up perceiving our family to be, a typical South and South East Asian family, emotionally open, expressive and unrepressed. There is some generational wound here, something which even my family will not touch and feels the need to push away. Delicately, I open its time-worn pages and begin to read.

Monday August 30th, 1808. Kampung Gunung, Penang.

Yesterday I made his favourite foods in the hope that it would soften him- ikan bakar in banana leaf, ikan bilis and sago gula melaka. I spent hours making them just right, according to Ibu’s recipes- melting the gula melaka sugar to the perfect consistency on the stove, pounding the chillies for the sambal, picking the fattest fish from the market to steam- but when he came home he complained that the whole house and I were stinking of belachan and that now he would go to work tomorrow stinking of it too.

And my shame almost swallowed me today when I met Aida, my new bidan midwife. She is young for a bidan, and so she does not have much of a reputation, but she is all I can afford. She is kind and beautiful with dark, clever eyes. She found some of the bruises and wounds that I am normally able to hide as he is careful enough to make sure these are on the private areas of my body.

She told me that if he continues like this I will lose the baby. I don’t know what to do.

I wish I could run away to the tops of the mountains.

Friday September 3rd, 1808

Allah have mercy on my soul for I have lost my mind! I cannot describe or believe what has happened. It cannot have happened. I must write it down. Perhaps I can make sense of it if I write it down.

There was so much blood, blood all over the bed. When he saw what was happening he left me and the baby there to die, in agony. I could see the moon through the window and hear the breeze and then through the smell of blood and sweat, the stench of vinegar. I thought I heard a baby crying. When I looked at the window there was a face staring back at me, a woman’s face as white as the moon with long dark hair and eyes rimmed with black. And where her body should have been, there were slick, glistening, bloody organs, a beating heart, two throbbing lungs, tubes of intestines, exposed dangling viscera.

The next moment she was in the room, her face and her long hair leaning over me. “You will be saved,” she said.

When I woke up the next morning, all the blood was gone. My nightdress and the bed were clean, white and damp only from sweat.

I found enough strength to prepare dinner for him, just in case, but he never came. I sat alone at the table and despite everything, for a moment, I enjoyed the warming laksa soup, and slurped my noodles like a schoolgirl.

That evening I went back to Aida’s house, which like ours was a rumah panggung on stilts, though hers was closer to the wild mountains on the outskirts of the kampung village. The water around the house was still and glittered in the moonlight. Drawing closer, I heard the growling of a tiger or a black bear coming from the forested hills. The lights in the neighbouring stilt-huts were out.

“Aida,” I called after climbing the steps to her porch. “It’s Maeena. Please let me in.”

She opened the door in her nightdress. Her clever eyes were lit with both concern and curiosity. “Of course Maeena, come in.”

She sat me down on a wooden chair in the corner of the room and brought me a glass of kopi cham. The mild stimulant helped soothe my nerves, but there was something about the house that was making me uneasy.

“Aida, I think I may have lost my baby.”

“Yes, Maeena. You have.”

I began to wail. “But my cantik,” she said. “You have also gained life.”

“What do you mean?”

“Your husband has left you, yes? He has run back to his mother’s village to torment the next woman. And you are still alive.”

“Yes,” I said looking up at her. “But what if he comes back? What if he doesn’t? I don’t know which is worse. I won’t survive without him- I will starve.”

“No you won’t, my cantik. I know a way for you to survive, and be happy, and free. Freedom- that is what you want more than anything, isn’t it?”

I nodded.

“And you shall have it. I will teach you the ways and rites. But I must warn you- this path is not without its own pain.”

I listened carefully. “I am sure it is no more painful than the life that awaits me otherwise.”

She nodded. “I know. It is why I have wanted to show you since the moment I met you. Follow me.”

I followed her into a back room, through an archway with a curtain of finely painted beads. Before us within the wooden framework was a bathtub surrounded with candles. And that was when I realised what had made me uneasy. It was the smell of vinegar. Under her frangipani perfume, Aida reeked of it. In front of us, the bathtub was full to the brim with it…

“Isha, we’re nearly here, this next stop is for Brasov.” One of my colleagues who was travelling with me was standing in the aisle with his bags, leaning over my shoulder. “Wow, how old is that book?”

“About two hundred years old,” I said, shutting it and getting my belongings together.

“What’s it about?”

“It’s an old family heirloom.” I thought back to the stories my aunt had told to me when I was a child. “I think it’s about an old Malaysian myth. Kind of like our version of a vampire. It’s called a Penanggalan.”