The following story is part of a set of “mirrors,” which aim to form a narrative history of disabled people’s experiences, excavating lost voices and highlighting what has and has not changed.

All of the freaks mentioned in the following story are based on real historical people or an amalgamation of them.

The Closest Thing to Power

I

I was known as the Living Torso, The Amazing Half-Boy.

I was born a living, breathing monstrosity: a freak of nature.

Such terrors must be explained. So the story went that my mother, having been abandoned by all the men in her life, by her father, her husband, her brother, that God took pity on her and gave her child who was born without legs so they could never leave her.

Such terrors must be explained, and it was said that as my mother was continually abandoned, first as a child by her own father, and later by her husband, she was granted a consolation from God: I was born without legs, so I could never leave her.

But I did leave her; I left her to join the Sideshow when I was 15 years old- and I became a legend.

Oh yes, I had quite the illustrious career in showbusiness. I became wealthy enough to buy my own home. I even had a beautiful wife and family, and how I was able to accomplish the latter was a matter oft-speculated on in the papers and scandal rags. Not too shabby for a small-town Irish immigrant, fleeing poverty in the wake of a Famine which claimed the lives of stronger men than I.

They said I should have been strangled at birth, but I was a relentless survivor.

I learnt my first trick when I smuggled myself onto a ferry by hiding in a suitcase and spent my early career begging on the streets, giving a free show as I walked on my hands and rolled cigarettes with my mouth. My main concern in those days was having enough bread to eat and avoiding the workhouse and institutions built for people like me. They used to stare at me in terror, ridicule and humiliate me, throwing oranges and rotten eggs; it turned out that I was more threatening to them out on the streets, trying to blend into the crowd as if I had the right to be there and make a living as one of them- but up on the stage, taking my place with the other human curiosities, I was a spectacle of wonder, a performer; they gazed at me in fascination, and whether their stares belied disgust or delight was not my concern; they had always stared at me, but for the first time, I was getting paid for it.

There is a power in being able to command people’s attention. It’s the closest thing to power I’ll ever know.

I found a true home and belonging among the other freaks, unlike anything I had ever experienced. The Skeleton Dude, John Coffey, was a good friend of mine. He was as I am, a fellow Irish degenerate, and he looked as deplorable as any of the deathless sacks of bones one could see dragging themselves about during the Famine, but I’d seen him devour more food in one sitting than the Bearded Lady of Geneva or the Irish Giant, née Patrick Murphy, put together.

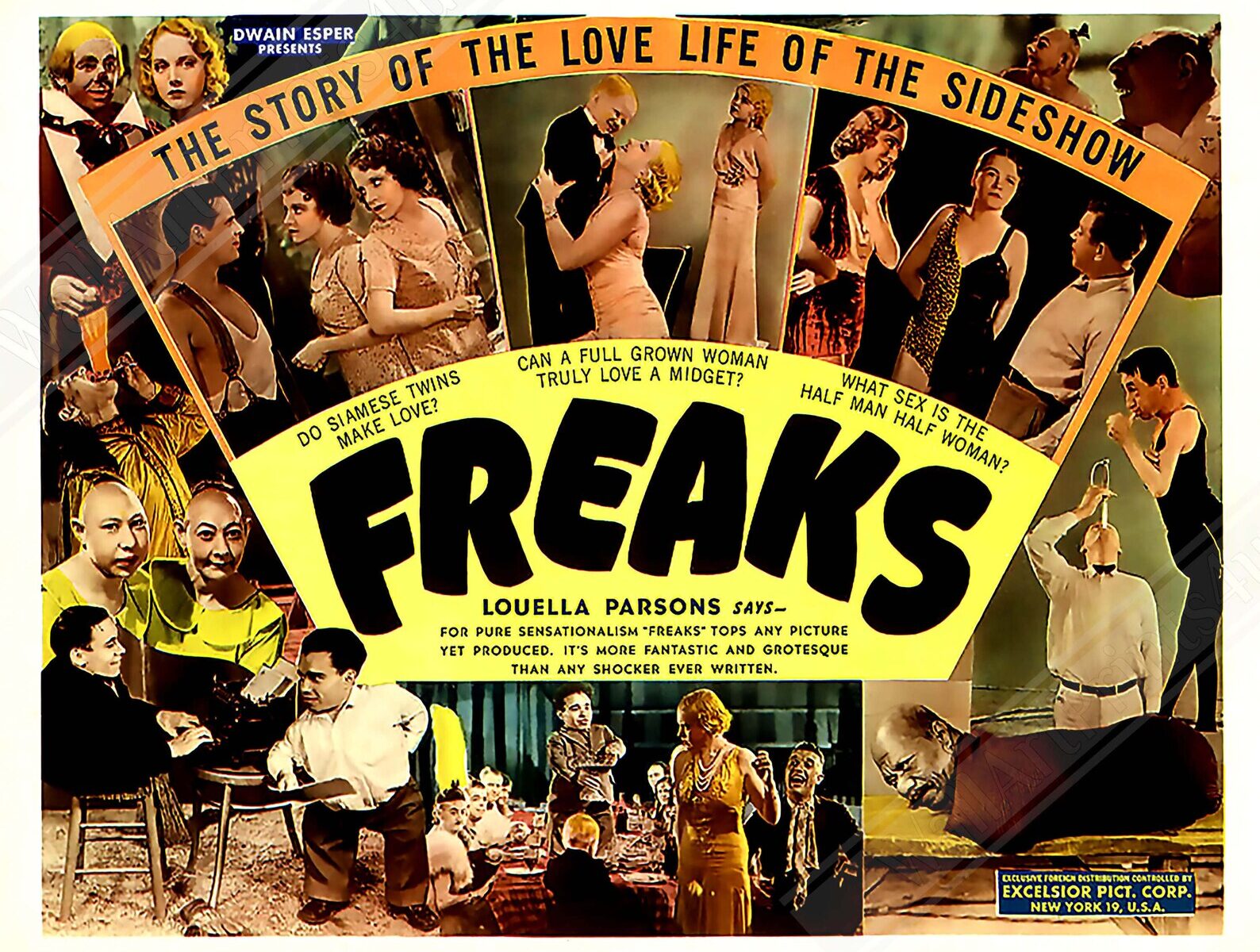

I once opened for Chang and Eng, the inseparable Siamese Twins, and shared the stage with Sealo, who had flippers for hands, and the Dog-Faced Boy whose face was hairier than the curls on the chest of the Strongman.

I liked to play games with the Pinheads, who seemed to us perpetual children. I believe they were removed from a mental asylum, along with Koko the Bird Girl. Who will ever know which cages they preferred, the institutions or the bars that held them on stage, the bars they thrashed against in their supporting role as primitive ape-men. We all existed somewhere on a spectrum between human and animal, but the Pinheads and the genuine African exhibits were the most exotic freaks of our merry band of depraved and deformed cast-offs.

I have seen our kind subjected to much violence, out there in the grime- in the circus ring we have some degree of protection. That is not to say that freaks are always kind to each other, or that the carnie life is as romantic as young runaways suppose. A callousness reveals itself when freaks are up the pole with beer. I was there the day they humiliated Tom Thumb in front of his little wife Lavinia. They sat him on the shoulders of the Hermaphrodite and carried him all the way to town, refusing to let him down despite his tormented pleas. He would have been arrested or murdered by the townies had not the sorrowful Irish Giant, the Bronnach, frightened them with his stature and stolen Tom Thumb back to the circus.

The sideshow has taken me farther afield than I ever thought possible: I have played to packed-out audiences in London, America and across Europe. But when my two children were born, I began to retire from the stage, making only the odd appearance to sustain our now rather modest wealth. Yes, many once-affluent freaks have died penniless, robbed and deceived by managers or crooks; showbusiness is a ruthless profession.

Our drawing room walls remain lined with posters from my sell-out shows. “Come See The Most Astounding Man Alive!” They proclaim. You can see me playing the grand piano dressed as a gentleman in my trouser-less jacket and waistcoat. No one has ever seen the tiny, deformed limbs I hide inside it; it contributes to the half-boy illusion of course, and this way I appear quite dapper, and not quite the freakish monster they expect. Yes, I am proud of them; I am proud of my adventures in the sideshows. But I do not want my children to follow in my stead. We would have made quite a spectacle as the real thing, unlike the many staged freak families- but the thought of seeing my children paraded like that the way I was, is somehow distasteful to me. I hope they will have better options to make something of themselves than I did. In quiet moments, when I am honest with myself, I see that I was nothing but a penniless scoundrel who exploited the only thing available to him- a body deemed so hideous, that it made him a star.

II

They called me Duck Boy, after the mutant character Ducky in Toy Story. He had the head of a duck, which I don’t have, on a torso body, and walked with his hands, which I also do. I was born with sacral agenesis, or caudal regression syndrome; this means that the lower portion of my spine did not develop fully. I still have legs, but I’m not able to walk with them and prefer to use a wheelchair or move around the house on my hands.

I am proud to be disabled, but I didn’t always feel this way; I used to feel ashamed of how I was formed. The taunts of the children in the playground still haunt me; when I walk down the street people still stare and gawp and yell out “freak.”

My family and I were always worried about how I would survive and make a living, and I have struggled to find work and get off disability allowance. But three years ago, I appeared on the reality TV show “Undateables,” and since starring in that series, my career has taken me in new directions I never thought possible. I am effectively a minor celebrity, though not very well-paid. I’ve been on quite a few chatshows, reality TV shows and documentaries, one which just follows me in my day-to-day life, and I campaign for disability issues.

I have yet to meet anyone with my physical condition: the only people I have heard of with sacral agenesis were freak performers in Victorian sideshows. This rarity makes me, in a sense, more valuable in front of the camera, though I doubt I have the appeal of say, Abby and Brittany Hensel, the conjoined twins whose reality show made them truly famous.

Sometimes I wonder if I should feel exploited for being a “poster child”- but if I can earn a bit of money and draw attention to the causes, I don’t see any harm in it. People have always stared at me growing up, and when I perform or stand before the camera, I feel in charge of what used to be an oppressive situation. I feel I am owning my own power; it’s an act of self-love and acceptance. I love my body, I see it as normal, and I hope that if people are more exposed to different bodies, then maybe one day, eventually, they will come to see us as normal too. Perhaps it’s a naïve hope.

I still long for a romantic connection and to start a family. I do know of plenty of people in the disabled community who have married and had kids and led relatively normal lives, despite the title of the show I was in, but I have struggled with dating myself. I had a girlfriend for two years after the show. She was non-disabled and at first, I couldn’t believe that she would find me attractive. It was a form of validation and made me feel recognised as normal for the first time. She was the love of my life, but she moved to Australia, and we couldn’t make the long-distance work. I was too afraid to leave Ireland and lose my disability allowance and medical card. Perhaps one day I will move to LA where the bigger studios are, though either way I doubt I will ever be able to afford a home.

My Tinder profile used to have a picture of me in which it was not immediately obvious that I was disabled. I once experimented by not giving a girl advance notice of my impairment. I showed up at the restaurant, giving her no choice but to reveal her instinctive reaction, and sure enough her jaw dropped. She laughed horribly as she took a picture of me and sent it to her friends, and as she left, she patted me on the head as if I were a child or a dog, a docile animal, something subhuman.

Since appearing on TV, I can no longer hide my disability- every prospective date knows how to Google- and I wouldn’t want to. It’s part of who I am and I’m not ashamed of it.

I have recently found a great sense of belonging in the disabled community and the independent living movement, in connecting with others who are like me. Perhaps we can improve our situation by collective action.

If I ever have children, I hope that they will never have to be in a show called “Undateables.” I hope that some day, our bodies will be normalised and we will finally be seen as fully human. I want to still be around when that day comes.