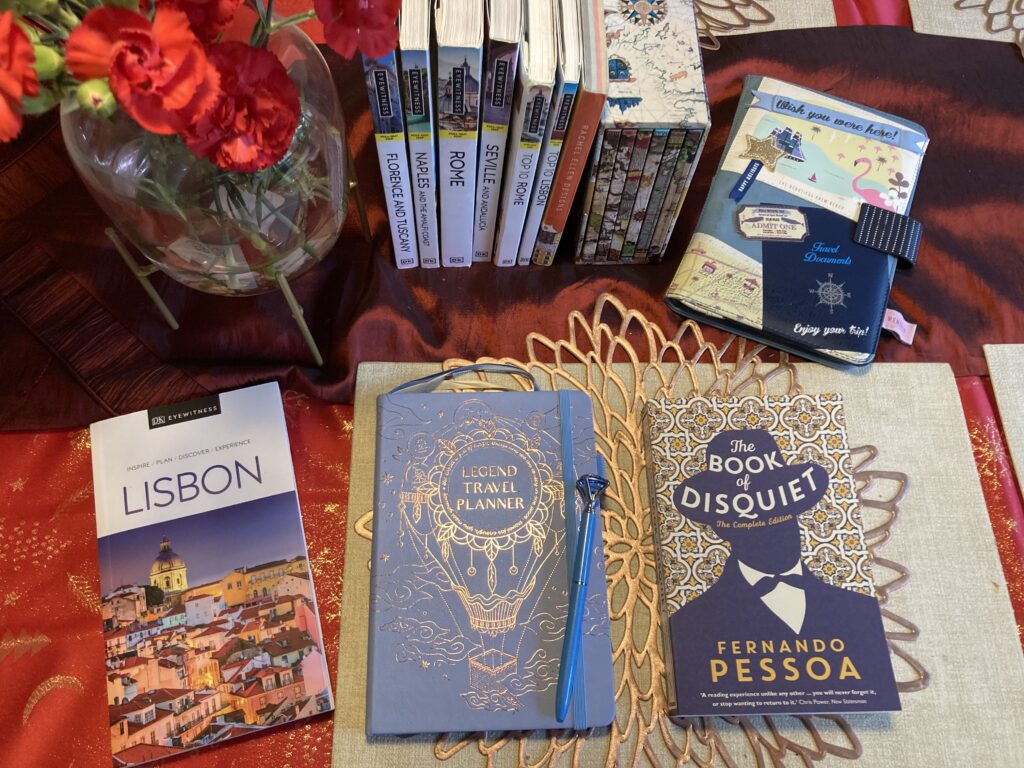

An assortment of travel planning tools and books to dream into: a Light Blue Travel Planner for Lisbon, DK Eyewitness book, and chosen novel for the trip, The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa. In the background, part of a collection of DK Eyewitness books from my most recent and upcoming trips, some travel notebooks and travel pouch.

“I think hope lies in the very nature of travel. Travel entails wishful thinking. It demands a leap of faith, and of imagination, to board a plane for some faraway land, hoping, wishing, for a taste of the ineffable. Travel is one of the few activities we engage in not knowing the outcome and reveling in that uncertainty” –

Eric Weiner from “Why Travel Should be Considered an Essential Human Activity“

Why You Should Let Yourself Start Travel Planning Right Now

One thing that has helped me to stay afloat and recover from burnout in these last few stressful years of festival, parade and community organising, has been travelling. Since moving out of our apartment last year, we have spent our rent money on adventures instead, and it’s a short-term choice I’ve found extremely nourishing- already looking back throughout my life, these experiences and moments stand out as stark reminders that I have lived, and lived well.

Travel is a gift and a privilege, but it also fulfils a very essential need and yearning in us. To travel is to immerse oneself in wonder, which rekindles our awareness of how strange and precious it is to be alive. It is a reminder of how big and beautiful the world is. It expands our minds in witnessing the myriad ways that humans have lived. And for disabled people, it is essential to fulfilling our need to experience freedom.

There are many ways to see the world on any kind of budget. Once I hit my thirties, I realised that if I didn’t make a start on seeing the world now, I likely never would journey to all the places I’ve always wanted to. And while travelling may not be accessible to you right now, travel planning most likely is.

A twin and often-overlooked companion to the travelling experience is travel planning. It costs little- only the price of a travel planner and guidebook, some internet access, and time. I recommend to always have a holiday you’re planning in the background- it gives you something to nourish your imagination for moments when you need an escape, and it is a joy in itself.

Why Travel Planning Beats Spontaneity Every Time

There are two kinds of travellers, as there are two kinds of writers- plotters, who love a good itinerary or plot outline before writing or travelling, and pantsers, who love to fly by the seat of their pants. And while it may work better in pure flights of the imagination, planning for travelling wins out every time. That’s because the amount of nasty surprises and extra expenses that can be thrown at you gets halved- and particularly as a disabled person, there are a whole host of extra nasties that can come up when travelling that non-disabled people don’t have to think about, including for example, if your hotel and the street it’s on is fully accessible, if the attractions you want to visit are accessible, if you can get inside the restaurants where you want to eat- I think you get the picture.

How to Travel Plan Better- Step 1. Choose Your Travel Companions Wisely

Who you travel with is just as memorable as what you do. Make sure to only travel with those you feel comfortable with, and if you are introverted, it’s ok to ask for some alone time to visit a cafe or a site by yourself.

While my partner and I may not have a perfect relationship, we truly are perfect travel companions. My love of researching for a trip and developing itineraries matches his easy-going nature, and he is always happy to go along and try something new, without being affected by any stress I might exhibit bearing the mental load, while he handles the physical load, pushing my manual wheelchair up great distances and inclines. This current trip is for his 40th birthday, and I have kept the location a surprise so he can show up to the airport not knowing where we’re going!

Step 2: Planners and Guidebooks

Once you’ve decided where you want to go from your bucket list and looked up flights and where is cheapest around the dates you’re thinking of, then the real fun begins. I like to start by ordering a DK Eyewitness Book (not sponsored!) such as their Top 10 city series, which are usually very detailed, and help to give you a sense of the areas of the city and must-see attractions. I recommend also ordering a detailed travel planner with space to record not just your experiences, but sections for your itinerary, packing, and space for lots of research including the places you want to visit and eat in, based on vicinities and neighbourhoods.

Step 2: Deciding On The Best Area to Stay In

Reading through your guidebooks will help you to get the lay of the land. Particularly for disabled travel, you will want to prioritise spending a little extra to be in the centre of things and closer to the attractions you want to see.

For our upcoming trip to Lisbon, I’ve chosen the Baixa district because it is one of the only parts of Lisbon (along with Belém) that is flat, without trams to get up the heart-stopping San Francisco-esque hills. (Lisbon, like Rome, was built on seven hills- the Baixa is flat only because it is the most modern, and was rebuilt with wider, safer streets by the Marquis of Pombal after the 1755 earthquake and tsunami combo devastated the city- and had ripple effects all the way here in Ireland, creating the Aughinish Island in Co. Clare!)

I also like to have a quick look on Happycow to see what areas the best vegan restaurants are in, and to create a food bucket list of restaurants I’d like to visit.

Step 3: Hotel and Accommodation Tips

Once you’ve decided on the area you’d like to stay in, you can look for accommodation on booking.com and Airbnb. Some tips for this:

- Avoid Airbnb if you can– it is contributing to housing crises across the globe, with tourists staying in apartments, and homeless people staying in hotels as emergency accommodation. As in Dublin, locals are being priced out of apartments due to housing shortages and remaining housing being used for Airbnbs. There are times though when Airbnb will be a lot cheaper, for example with significant discounts given for stays of over a month.

- Check the Hotel’s Website for Potential Discounts– Booking through the hotel’s website directly often saves you fees of 10% or more. We are able to afford Brown’s Central Hotel only through their website, which has huge price differences with a January discount.

- Benefits of Staying in More Than One Hotel– you don’t have to spend your entire trip in the one place. If you really like the look of a particular place but it’s not available for your full stay, experiment with splitting the dates. You may then be able to afford a more expensive hotel for just a few nights. Staying in multiple places during your trip can also help you get to Booking.com’s Genius Level 2 or 3 for significant reductions. Make sure to book on their mobile app for further reductions. You need to complete only 5 bookings over two years for Genius Level 2, and 15 stays over two years for Genius Level 3. Just make sure to avoid changing hotels too often as the check-in and out process can eat up your travel time.

- Read All the Reviews– it’s important also to read the reviews carefully, and keep an eye out recurring complaints around noise levels or hygiene. Aim to go for as high a rating as you can (ideally around 9 on booking.com). In the Reviews you can also find more details about stairs and accessibility which may not be clearly shown in the listing.

- Access Check– As well as reading the reviews and contacting the hotel directly, you should also check the street view of google maps around the hotel.

- Proximity to Attractions and Restaurants– As well as its centrality to attractions and public transport to reach other areas, check your hotel’s proximity to restaurants and cafes that you’d like to go to. Unless exceptional breakfast reviews are shown (such as the very best vegan hotel breakfast we ever had in Niki Athens Hotel) you are better off having a delicious fresh pastry in a cafe around the corner if you are near one.

Step 4: Fool-proof Formula for Itinerary Building: Group Attractions and Food to Create Area Groupings

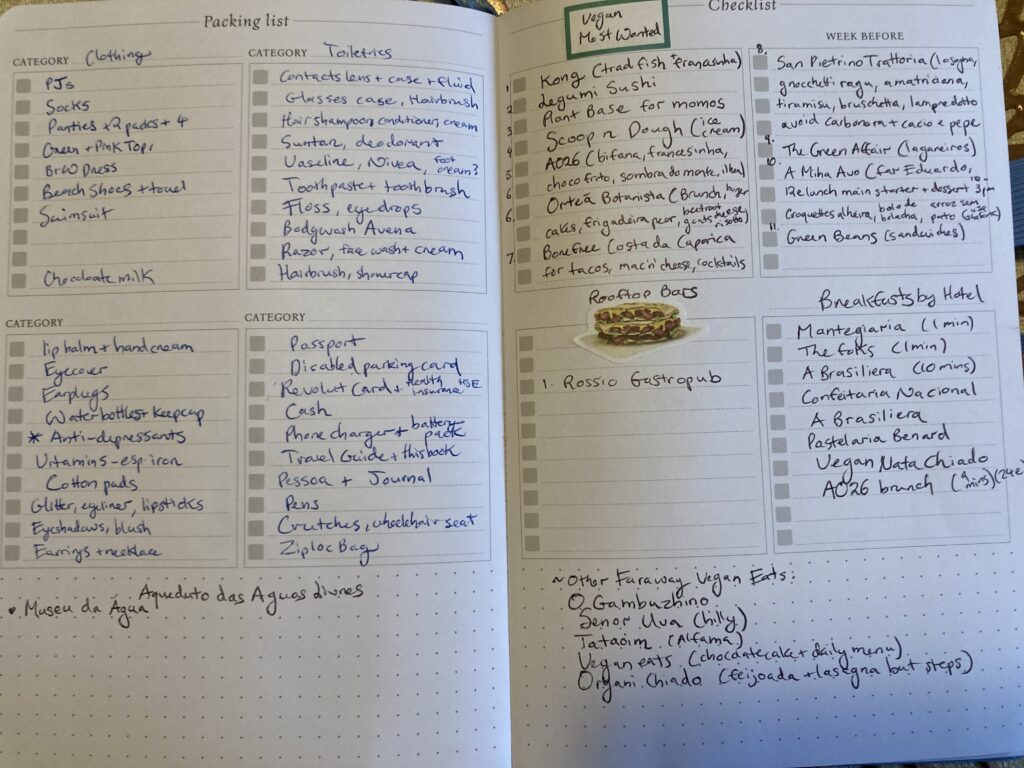

My fool-proof way to start building your itinerary is to list the attractions you most want to see, then link the areas they are in with food and restaurants close-by. What you’ll end up with is a list of neighbourhoods and areas of the city with attractions and places to eat when you visit them.

This then becomes the bulk of your itinerary- you know what to do in each area, which then becomes a plan for the day.

Make sure to look up opening times and hours and especially as disabled people, check for free and reduced entry! Bring a Disabled Parking Card or a GP note if you have one for the oft-required though problematic proof of disability.

Here is an example of an Area Grouping:

Estrela Neighbourhood:

- Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (free entry for disabled people and companion) (closed Mon, open till 6pm) (Bosch’ “Temptation of St. Anthony” on Level 1, Room 1)

- Museu da Marioneta (closed Mon, last entry 5.30pm) (Reduced 4.30e disabled and free for companion)

- Legumi Vegan Sushi (13 mins from Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga) (Open for Lunch Wed-Sat, 12.15-2.30pm; dinner Tues-Sat, 6.15-10pm)

- Clube de Journalistas (Open Lunch 12.30-3pm, Dinner 7-10.30pm) (expensive)

Step 5: Other Lists to Add to Your Area Groupings

Here are some other things to look up in the area to add to your Area Groupings:

- Check Viator and Airbnb Experiences: For some of the most memorable things you can add to your trip, such as cooking classes, kayaking or adventure tours, craft workshops- we decided to book a tuk-tuk ride through Alfama since this is not an area we can walk around. Although usually expensive, experiences are often the most memorable parts of a trip. Just make sure it’s not a tour you can DIY- for example, with a bit of research, I’ve decided to stay in Sintra for two nights, travel from Lisbon by train, and Uber to the various attractions slowly over a few days rather than paying over 80 euro each on a day tour of the region.

- Viewing Points for Sunsets and Rooftop Bars: One of the first things I look up (after the top vegan restaurants on Happycow) for a new city are the best places to go to get an overview and watch the sunset. It’s a great way to truly take in a place. In Lisbon there are multiple miradouros, however most don’t seem accessible- we will instead take public transport to attractions such as Castelo de São Jorge, and might splurge on a drink at the Rossio Gastropub rooftop bar, though there are plenty of ways to catch sunsets for

- Bookstores & Historic Literary Cafes: One thing I always love to look up. Top on my list of these for Lisbon are the Ler Devagar Bookshop in LX Factory, which seems to be Portugal’s Shoreditch, and A Brasiliera, which was the haunt of Pessoa and home to his statue.

- Traditional Dishes to Try: Your lists should also include the regional dishes you’d like to try, and where you might find veggie versions. For Lisbon, this is of course pasteis de nata, but also veganized versions of Porto’s Francesinha, Bifana and Bacalhau a Lagareiro.

- Opening Days and Times and Free Disabled Entry: Worth repeating in bold here, that most countries offer free entry or discounts to disabled people and/or their companions for national attractions (Ireland is now one of the worst for this!). Most of the main attractions in Lisbon are free for disabled people or at least free for a companion, but as with Italy and Greece, you must bring some kind of proof of disability (which is an issue in itself). At least in Portugal they ask you to prove that you are 60% disabled, not 100% as in Italy (which in reality you can only be if you are dead). Don’t get caught out on opening hours- in Portugal as in Italy, most attractions close one day a week, usually either Monday or Tuesday.

Step 6. Create a Flexible Itinerary

Once you have grouped the places you want to see by area, ways to spend a day focusing on each area will naturally emerge. You can see my planned example itinerary at the bottom of this page. Keep it as flexible as you can, allowing time for rest periods, and knowing that you can swap your Day in Belém with your Day Trip to Costa da Caparica via Ferry to Cacilhas around, depending on weather and energy levels on the day.

Step 7: Book Restaurants, Tours, Experiences & Attractions in Advance

If you are quite keen on any particular restaurant, I highly recommend making bookings in advance to avoid disappointment. This is especially the case in cities like Rome. Vegan restaurants usually aren’t busy enough to require bookings, but there are always exceptions, such as this authentic-looking trattoria in Lisbon which has little availability and was almost booked out three weeks before the date I wanted for us. Well-known places such as Prado also require advance bookings to avoid disappointment and time wasted travelling to it (though you now have an idea of other places you’d like to eat in the area without having to spend time searching for one through Google Maps on the day!)

Usually for disabled people where there is free entry, advance booking isn’t required for attractions, where you can usually skip the line and tickets can be picked up at the ticket booth- for non-disabled people, this is not the case, and you are much better off booking tickets for big attractions in advance to avoid nightmarish queues in places like Rome, Florence and Verona. It also means that specials such as the Lisboa Card are not really needed for disabled people and companions, but if you are travelling with other non-disabled people, definitely book in advance and purchase similar passes.

Step 8: Language Learning, Movies and Media

It’s always worth picking up just a few phrases at the very least before travelling. I quite liked this survival Portuguese tutorial from Dave in Portugal on Youtube. I recommend Babbel Live for more in-depth learning to attempt to converse in your country of choice, once you have reached A2 level.

I love to get my hands on anything I can get in relation to my chosen country- any movie set in the place, such as Night Train to Lisbon starring Jeremy Irons, and based on the based on the novel by Peter Bieri, which you could also read. You can also see great episodes about Lisbon on Channel 4’s Travel Man with Richard Ayoade, and Somebody Feed Phil on Netflix.

Last Step: Choose Your Holiday Read!

The last thing to choose is your holiday read, and what book you’d like to take with you on your trip! You can usually find great suggestions online. I used this article for Portugal, and settled on Fernando Pessoa, intrigued by his concept of “heteronyms” and multiple identities.

I also usually pick up one more book as a souvenir in the country I visit. I will be looking for one of Jose Saramago’s works while there, and if time allows, we may take a gander in either of the Foundation Museums dedicated to these writers in Lisbon. Aware of the tendency for men to be more idolised in Portugal as in many other cultures, this book focusing on female Portuguese writers also looks wonderful.

Bonus: My Flexible Itinerary

Putting all this together, here is my flexible itinerary for Lisbon. I’ll share the actual itinerary of what really happened after the trip:

Lisbon Itinerary

Mon 29th Jan

Arrive in early evening at 4.10pm, get the train from airport to Rossio Station, then check in to Brown’s Central Hotel (roughly at 6pm)

Have a nice dinner in Plant Base around 6.30/7pm (order momos dumplings)

Pop into Duque du Rua Fado Bar by the hotel to make a reservation directly for during the week or the last nights.

Walk up to Scoop n Dough for Dessert

Tues 30th Jan

Long leisurely brunch OR nata in hotel room (From Vegan Nata Chiado, or visit A Brasiliera)

Tuk Tuk Ride by Bruna (recommended through a friend) around Alfama and Praca do Comericio from 1-2pm. Drop off at Castelo Sao Jorge for vista views.

Bus back to Baixa. If time, see Santa Justa Elevator and Carmo Convent (closes 6pm)

Try Ginjinha in Ginja Sem Rival

Tram or Bus back to Chiado for dinner in Kong

Wed 31 Jan

Brunch in The Folks OR Green Beans for Sandwiches and Nata

Trip to Belem and Jeronimos Monastery

Nata for Jules in the historic Pasteis de Belem

Visit the Torre de Belem and Padrao dos Descobrimentos (decide whether we want to pay for the lift and museum inside)

Pop into Museu dos Coches, just the Royal Riding Building Arena and if time, MAAT for beautiful exhibit.

Back into town for dinner in AO26 or The Green Affair

OR if too hungry, snack/dinner in Pateo or MAAT restaurant in Belem first

Thurs 1 Feb

Breakfast in the Time Out Market

Cais do Sodre ferry to Cacilhas

Bus ride to the Costa da Caparica

Lunch in Bone Free before or after a swim

Bus Back to Almada, See Cristo Rei and Ride the Boca do Vento Elevador

Dinner at Ponto Final

Potentially visit rooftop bar in Cais do Sodre

Fri 2

Brunch or nata e.g. Fabrica de Nata

Day Trip to Sintra- train from Rossio, check into Chalet Saudade (note, no fully wheelchair accessible bathrooms)

Lunch in A Praca (closes 4pm, closed Sun)

Take the 434 Bus and/or an Uber to Pena Palace, and then to Quinta da Regalieira

Dinner in Sintra e.g. Mela Canela or Incomum if after 7pm.

Sat 3 Feb

Breakfast from Hotel in Cafe Saudade

Uber or Bus 435 to Monserrate Palace

Dinner in Flores do Cabo

Sun 4

Visit Sintra National Palace and go around Sintra town.

Try Travesseiros and/or quiejadas in Piriquita or Quiejadas da Sapa

Lunch in Mela Canela

Get the train back home

San Pietrino Trattoria in Alfama Booked for 9pm

Mon 5

A Brasiliera or Mantegiaria for Breakfast

Parque Edoardo and A Minho Avo for 12e Lunch

MAAT Gallery exhibition if didn’t get to go.

If you did, visit the Aqueduto das Aguas Livres and walk along the top via the Museu da Agua.

Dinner Ortea Vegan Collective/Botanista

Tues 6

Breakfast at Confeitaria Nacional

National Gallery of Ancient Arts beside Puppet Museum, and Big Vegan Sushi Lunch at Legumi

Enter Elevator on Ponte 25 de Abril Bridge for Views of Sunset

Visit LX Gallery and Ler Devagar Bookshop

Fancy Last Dinner in Prado at 9pm or Clube do Journalistas

Fado Music in Duque du Rua after booking it on the first day.

Wed 7

Breakfast at your Favourite Spot during the holiday

Check out at 11am. Leave Bags in Hotel.

Lunch in a place you didn’t get to visit yet

Visit the Museo Nacional do Azulejo close to the airport

Flight at 8.10pm (leave for airport at 5.45pm)