This article was written in response to the Late Late Toy Show in November 2020

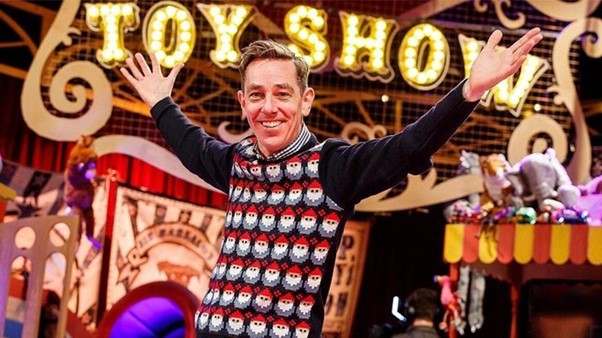

Image shows Ryan Tubridy in a Christmas jumper with santa hats on it, smiling and arms outstretched, with “Toy Show” in bright lights behind him

This year’s Toy Show was, in some ways, perhaps the most uplifting and successful in living memory; this year more than any other, the nation was hungry for a boost of optimism and Christmas cheer. I gathered with my family in my Christmas pyjamas like I have every year since I was a child, to soak up the glitz and glee. And I was uplifted as we all were, by the sentimental impact of seeing adorable children’s dreams come true, by the generosity of the Irish people and the comedy of Tubridy being a bigger child than the children.

But for me and many disabled people who I have since talked to, there was an element of the show that made us feel uncomfortable and disappointed.

Let me first start by saying that I commend the Toy Show for including more disabled children than ever before to review the toys. I believe the 2018 instalment was the first time a disabled child was brought on the show in this capacity, besides the usual pre-recorded Temple Street fundraising play montage. I was delighted then too to see books in braille being reviewed by a visually impaired child. This year was probably the first, in the twenty-odd years that I’ve watched the show, where children with other physical disabilities and wheelchair-users were brought in to review toys and it was incredibly heartening to see that change.

Last year Tubridy “made it his mission” to include homeless children on the show (which I was again thrilled to see being acknowledged) and who knows, perhaps next year will feature children in the abhorrent Direct Provision system. If this year was for featuring disabled children, then it is a good opportunity to start a discussion about how disability is shown in the media, and how far away we still are from a progressive understanding of what disability is.

Most people are not aware of the media models of misrepresenting disability. These are a foundational element of Disability Studies as an academic discipline. They include the Medical Model, the Charity Model, and Disabled People as Inspirational. All of these are opposed to the Social Model, which is the view that disabled people themselves prefer. The Social Model acknowledges that it is not a person’s impairment that disables them, but societal barriers. It is therefore used to support the fight for enhancing disabled people’s rights to full participation in society. The Medical Model treats the problem as being solely in the physical impairment and is linked to the Inspirational Model in that disability becomes a person’s duty and burden to individually overcome. It also implies that having a disability is tragic and it makes non-disabled people feel that they should be grateful for their comparative state of being.

Among disabled people, we do acknowledge that having to overcome societal barriers at every turn, including the pain of being seen and treated differently as a child, and endless barriers as we grow up, does require the development of strength and immense and often heroic character. The children who appeared on the Late Late Toy Show are indeed inspirational for what they have had to endure from a young age and the shining characters they are. No one can possibly diminish their heroism or question anyone attached to them.

In future, I wish to see all guests on the show participating and being treated equally, without the need for much demonstration of disability or mobility.

Our children’s hospitals should not have to struggle to raise funds in the first place; surely it is the duty of our Government to provide for the health and treatment of our children. How did we get to a place where this cannot be done without private funding and amassing of public donations?

The key point is to let this be an opportunity to spark discussion on how producers can make sure to sensitively involve disabled guests and media portrayal in a way which will empower and promote even more uplifting messages. Our understanding of what disability is begins in childhood, and the difficulties we face only increase as we get older. Let’s make sure our society is aware of the huge changes that need to be made at a structural and cultural level to really ensure the health, wellbeing and full participation of all our citizens.